This post was originally published on the now-defunct Clyde Fitch Report, a blog about art and politics, for which I wrote a regular column on comics and graphic novels. I’ve updated the post to correct its subject’s pronouns.

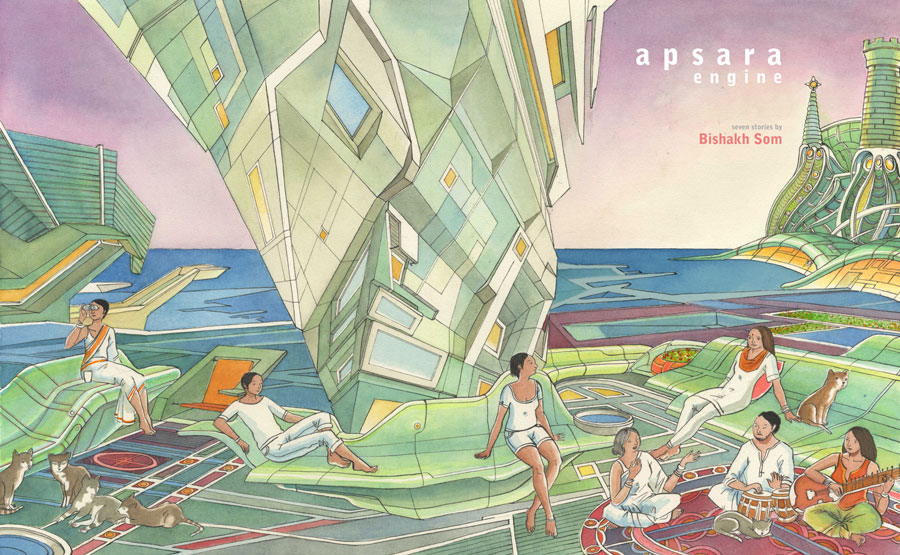

The artist herself: Bishakh Som

Bishakh Som, like her haunting, mysterious creations, is many things.

She’s a Harvard-trained architect. She’s an intellectual, a raconteur. She’s a figure in the independent comics scene (whether your degree of insider-ness causes you to spell it “comics” or “comix”). And if this is your first introduction to her work, I have a feeling it won’t be your last.

I first met Bishakh some time around 2004. I had been invited to a launch party for an anthology put out by Hi-Horse, a collaborative of comics folk of which Bishakh is a founding member. The cover of that anthology, the Hi-Horse Omnibus, featured an underwater scene drawn by Andrice Arp that included a giant, grinning fish, a contented-looking eel, and an octopus looking sternly at a submarine filled with tiny figures (while brandishing a bottle of moonshine). The Hi-Horse party was held, appropriately enough, at a sea-themed bar with a mermaid languishing in a giant tank behind a bartender who expertly doled out colorful drinks.

But Bishakh and I had actually been connected before this. We were both recipients of a grant for independent comic book writers and artists who were doing, in the Xeric Foundation’s estimation, interesting work (she won the award in 2003 for a collection of stories called Angel). Half grant, half cred-building award, the Xeric Award was established by Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles co-creator Peter Laird, an effort to promote independent work in comics. (The Xeric Foundation has decided, incidentally, to stop giving out the award after this year.)

By that point, Bishakh had been working in independent comics for some time, and was already an established and widely admired figure, rightly so. I was on my first book and no one had ever heard of me (also rightly so). But we both have distinctive names, so something registered in each of our brains somewhere. I bought Bishakh’s books, and she bought mine. Though our work couldn’t be more different, we could tell it was driven by similar forces, and we appreciated each other’s themes. When we finally met each other at the Hi-Horse mermaid party, the threads came together quickly.

It turned out that our commonalities go back way before 2003. We share a Bengali heritage, our work and worldviews inevitably influenced by India’s most proudly literary and musical culture. Both of us have been defined in ways by that identity, each of us having experienced the conflict of integrating our origins into our lives and creative work. Both of us grew up all over, our adventures of moving around and experiencing other places filtered through the lens of being third-culture kids and diplo-brats.

My father was a sociologist/economist focused on developing countries, and we traveled widely after my early years in India; Bishakh’s worked for the U.N., so they lived all over too—Bishakh was born in Ethiopia and grew up in New York. Bishakh and I can reconstruct and piece together a sort of misty map of Calcutta from our trips there over years to see our extended families. Looking up the addresses of our various relatives or places we grew up or visited in India, we’ve been surprised to discover that our families’ homes are within walking distance of each other. We bond over our memories of the sumptuous meals we’ve had in India, make long lists of Bengali sweets we remember and want some day to recreate.

Earlier this year, I had a small gathering to do a reading and celebrate the publication of the fourth book in my series of Malay ghost stories. This book, Sita’s Shadow and Other Stories, had been a long time in the making. In it, I’ve shamelessly ripped off Chaucer and used the device of different characters, passing time at an inn (although not in England, they’re somewhere near the Sunda Islands in the Malay archipelago), telling each other stories. The last of these revolves around a shadow play of the epic Ramayana, a story from my home culture that had made its way through what was once called “greater India”-the Southeast Asian peninsulas and islands that were so influenced by Hindu art and culture.

My father’s work took us to Indonesia in the 80s, and a love of that place will never leave me. My Malay series consists of weird tales and ghost stories I picked up while we lived there. Unfortunately, my father never got to see Sita’s Shadow completed. He passed away in 2009. The book is, of course, dedicated to his memory.

By a random happenstance, an architect friend of Bishakh’s got invited to my reading, and she came along with her—and so, after a few years of being out of touch, we reconnected. I found out that Bishakh had also lost her father in the years since I’d last seen her, and that she has continued working prolifically in comics, having most recently completed a cycle of stories called Apsara Engine. This new collection is, as we speak, in the hands of a few major publishers. (Author’s note: this exquisite book was published by The Feminist Press and you should buy it at once, along with her other work.)

My regular CFR column is to be focused mostly on comics, graphic novels, and visual storytelling. I couldn’t think of a better way to launch it than to share with you Bishakh’s beautiful work, her brilliant insights, and the enjoyment of chatting with her. To me, this is some of the best work being done in comics today, and a clear view into what this amazing medium can achieve and aspire to in skilled hands.

Your work is, in two words, ethereal and beautiful. It’s also disturbing. So let’s start with the inevitable “where do you get your ideas?”

The inspiration for my work comes from a variety of places. In some cases, an imagined situation or the idea of a certain kind of dynamic between two people will come unbidden to me-sometimes it’s as simple as thinking that I’d never seen a graphic novel in which contemporary South Asian women are the protagonists or a comic about a younger man falling for a much older woman.

So I take that lack as a starting point and develop a story from there. Lately I’ve been interested in sustaining a tone between two characters, exploring their personalities and dynamic through dialogue. I’d also like to try writing stories that are not so chatty and maybe involve more action (minus guns, fisticuffs and explosions) and/or playing with modes of representation within the medium of comics.

This is something I’ve been trying to do with the more architecturally oriented stories that use architecture and the idea of architectural landscapes as an organizing visual and thematic principle that can cross-pollinate with the language of comics. I’m occasionally inspired by a dream or by something that happens to me personally or by a revenge fantasy but not often.

As for the disturbing aspects of some of the stories, I guess those come from my love of horror films. But I’m not so interested in blood and gore, obviously-I’m more into exploring themes of psychological horror, disorientation, displacement, misfits…stuff that’s eerie but not necessarily death-focused.

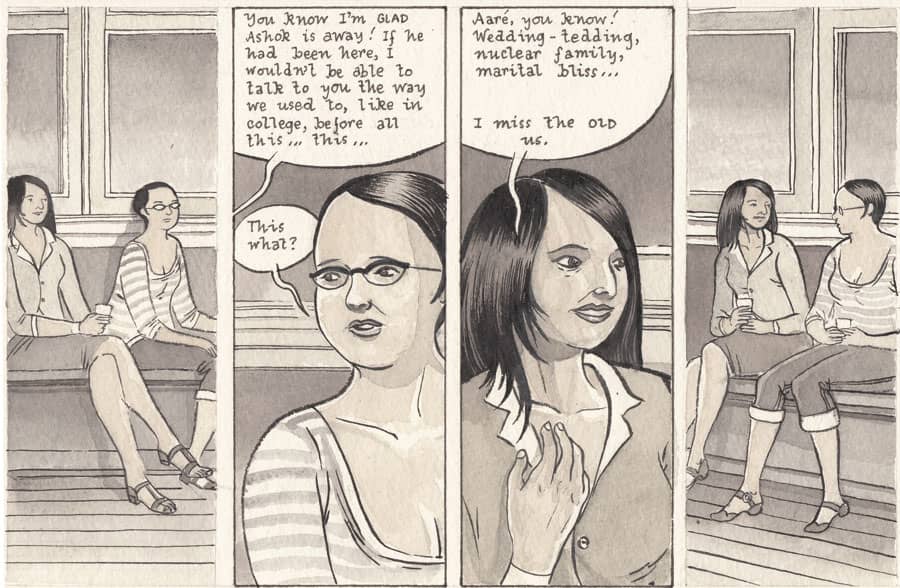

There are two stories from your Apsara Engine collection that jump to mind when you talk about this aspect of your work. The first is called “Throat,” which you told me was based on a dream, and features two friends meeting in a bar-one of whom casually shows off her pet, a dog with a woman’s head. The other is “Come Back to Me,” in which we hear the narrator’s inner thoughts as we watch her have a very unusual encounter. Tell me more about these?

A panel from “Throat.”

“Throat” was indeed initially inspired by a dream. I wanted to suggest a world-really to just take a peek into it-which was in every way like our own. Except for this one anomaly that it was somehow morally acceptable to keep these hybrid creatures as pets, to keep them on leashes, to infantilize them. I think the horror in that story comes from mining the gap between us as a species and our pets and what it means to take ownership of another being, especially if that gap starts closing.

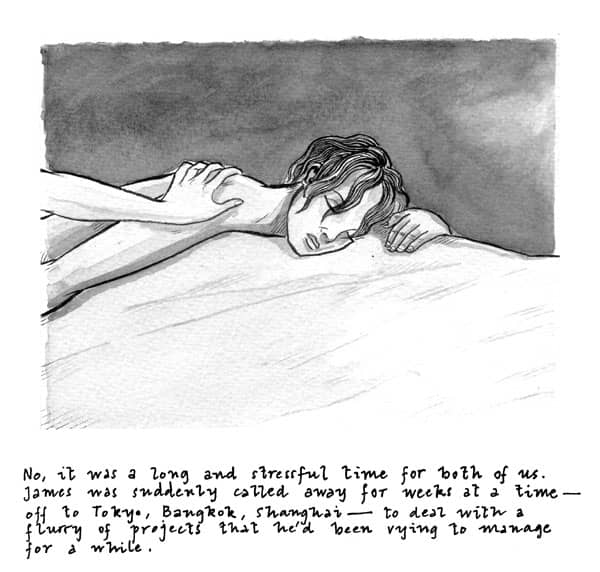

“Come Back to Me” is a little bit of a formal exercise in that the two linguistic modes that operate within comics-visual and textual (maybe a false dichotomy?)-initially seem to be in concordance but then begin to diverge halfway through the story. Which is a conceit that I guess underlines other thematic divergences within the story: stability vs. passion, subconsciousness vs. consciousness, and so on. It’s not really a horror story (in the same way your work isn’t), but the disquiet within it comes from a sense of distance that divides desire from reality, and how maybe our inner mind-worlds can dive into that distance and distort the space between.

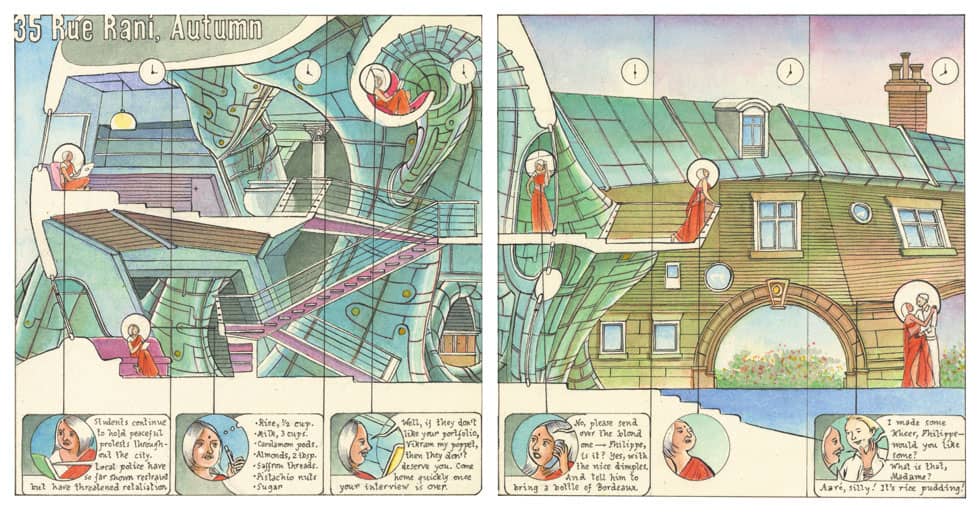

You mentioned your architecturally-themed stories. The use of architecture and landscapes, combined with your graduated watercolors, are a signature technique. Can you talk a bit more about how you use these environments in your stories?

I’ve been trying, as I mentioned before, to create a sort of hybrid visual language, one that straddles the worlds of comics and architectural representation. One piece in Apsara Engine(“Four Scenes”) is all about this hybrid mode.

Each of the four scenes in the piece is a single image (a city, a building, a room) presented using a different representational method (aerial map, isometric projection, section, perspective). Within each image, the characters inhabiting that space (or else the interior worlds of the characters) are “called out,” the way details are called out in an architectural drawing, and the relationships between the characters are traced visually, using graphic devices (dashed lines) or narrative implications.

In one image, the same character moves across the space of the drawing and simultaneously across the space depicted within the drawing, her movement implying the passage of time.

The other stories in the book aren’t so architecturally or formalistically oriented but I’ve tried to pay attention to the architecture in all of them so that the interiors or streetscapes that the characters inhabit aren’t just backgrounds but are palpable environments that also interact with the characters. In earlier efforts, I had tried integrating maps, building plans, diagrams, etc. into an otherwise conventionally presented comics story-something I’d like to explore again but within a longer narrative.

Which brings me to juxtaposition. This is something I love working with-and you’re right, comics is a perfect medium to experiment with decoupling images and text. What are some of the juxtapositions you’ve enjoyed weaving into your stories?

“Love Song” I think represents the most successful attempt at juxtaposing discordant text and image. The text, as the title implies, is a love song to a partner, but a bittersweet song that anticipates sickness and dissolution.

The images tell another story-a fairytale of sorts that involves a little girl, three birdlike creatures of varying degrees of oddness and a sense of ascension and epiphany at the end. You can, at points, draw threads through the words and images and at other times not so directly, but I feel like the overall texture and direction of both strands are similar enough that you feel that they work together. My earlier attempts at this sort of thing were probably too oblique and jarring (in the discordance between text and image) to make any meaningful connection to the reader.

What criticisms have you heard about your work, and what areas are you focused on developing further?

On two occasions I’ve heard that some of my earlier work was incomprehensible-mainly when I was experimenting with the text/image uncoupling, but also when I wasn’t so focused on narrative but more on atmospherics and lyricism. I think I was trying too hard to break out of narrative convention and to write songs or poems through the language of comix. I really liked one story I did early on in which the text was like a somewhat sappy but erotic ballad (I was aping early Kate Bush lyrics) while the images proposed something much nastier in the end (there was a succubus involved)-I got pretty much no reaction from it from anybody. I was managing to only not connect spectacularly.

That’s one of the toughest things about working in this or any creative medium. We don’t always want praise, but we all thrive on feedback-how else can we evolve and improve? What did you do after that, did you alter course?

After that I switched gears completely and focused solely on narrative and on conventional ways of presenting stories and later on started reviving the architecturally-focused work (which I think isn’t as opaque as the other experimental stuff). So now I’m happy working on both strands. I would love to begin work on a longer, book-length story that would tie these two threads together, combining a comprehensible narrative format with other methods of representation that would supplement (and maybe even at times take over) the narrative. But for now I’m just focused on finding a good home for Apsara Engine.

Who are some people working in the medium whose work you admire, and would recommend to our readers?

Growing up I was initially most influenced by Herge’s The Adventures of Tintin (as I know you were). If that rollicking sense of derring-do hasn’t translated itself into my work, I hope at least that the attention to architectural detail and physical context have, as well as Herge’s clarity of line.

Jaime Hernandez’s work on Love & Rockets in the 90’s also inspired me a lot; again for his clarity of line but also because of the warmth and realism of his characters. I wouldn’t be surprised if Hernandez was inspired by two of my favorite artists, Stan Drake and Leonard Starr, whose woman-centered stories from the 60’s with their depth of narrative tone represent a lost genre that I think my stuff attempts to revive in a kind of slanted fashion. Lastly, for sheer whimsy and elegance (stylistically and thematically), as well as extra goth points, both Dame Darcy and Edward Gorey are well ensconced in my book of favorites.